Introduction to forms based authentication in ASP.NET MVC5 Part 3

June 30, 2014 Leave a comment

Introduction

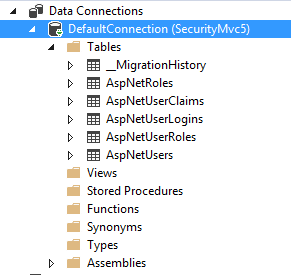

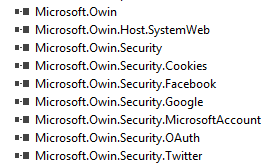

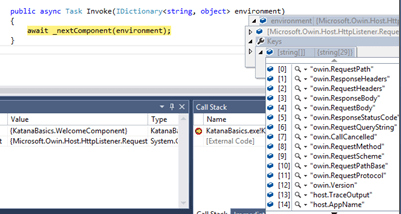

In the previous post we started digging into the components around Identity in MVC5. We looked at the default database and the Microsoft.AspNet.Identity.Core. We also saw how the MVC5 template with Forms based authentication creates a default UserManager class which can handle user creation, login, updates, claims etc.

We’ll continue our discussion with some other components around Identity in an MVC5 project.

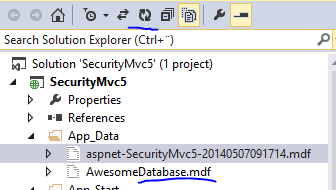

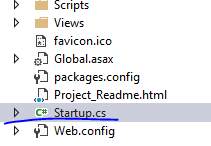

We’ll build on the demo application from the previous two parts of this series.

EntityFramework

EntityFramework is the default choice for storing users in an MVC5 project. As far as identity is concerned EF is encapsulated in the Microsoft.AspNet.Identity.EntityFramework package. Do you recall the interfaces around user management in the Core assembly? IUserStore, IUserLoginStore, IUserClaimsStore etc. The EntityFramework assembly provides the out-of-the-box concrete implementation of each of those abstractions. Examples:

- IdentityUser implements IUser

- IdentityRole implements IRole

- UserStore implements IUserStore, IUserLoginStore, IUserClaimsStore etc., so it contains a large amount of methods and properties which are implementations of the interfaces

IdentityUser and IdentityRole are entities that depend on EF for their persistence mechanism. Recall the database that MVC5 created for us in the local DB. Those are the DB representations of these identities. In AccountController.cs this UserStore is passed to the constructor of UserManager which in turn is passed into the constructor of AccountController. The UserManager will be responsible for all user-related operations through the UserStore implementation: insert, update, delete, add to role, read claims etc. If you navigate to AccountController.cs then you’ll see that the type of the user in the type definition is ApplicationUser. So what’s IdentityUser? If you locate the ApplicationUser class in Models/IdentityModels.cs then you’ll see that it derives from IdentityUser.

You can use the ApplicationUser class to extend the functionality of the default IdentityUser entity in EF with your custom properties.

There’s an additional important object in IdentityModels.cs: ApplicationDbContext which derives from IdentityDbContext of ApplicationUser. IdentityDbContext in turn derives from DbContext which is the standard object context in EntityFramework. Hence ApplicationDbContext is also a DbContext but it has access to the User related information that IdentityDbContext carries. We said that Users and Roles are entities so it’s just as well that ApplicationDbContext gets access to them. The constructor of the ApplicationDbContext object defines the name of the connection string, which is DefaultConnection. We saw this in the previous post but now we know where it is defined. In case you’ve renamed your connection string in web.config then you need to rename it here too.

ApplicationDbContext is also where you can add your custom DbSets so that EF can create the tables for you. We’ll go into EntityFramework in the series after this one so let’s not dive into that topic too much. It suffices to say the if you have a Customer domain then you can add a DbSet of Customer like this directly in ApplicationDbContext:

public class ApplicationDbContext : IdentityDbContext<ApplicationUser>

{

public ApplicationDbContext()

: base("DefaultConnection")

{

}

public DbSet<Customer> Customers { get; set; }

}

If you go back to AccountController.cs you’ll notice that an ApplicationDbContext object is passed into the constructor of UserStore. Now we know that ApplicationDbContext derives from IdentityDbContext. IdentityDbContext is the EF object context which will carry out the actual DB operations of SELECT, UPDATE, DELETE etc. If you’re familiar with EF then this object context class will sound familiar.

You’ll also notice the TUser generic type argument. The actual type provided in all cases is ApplicationUser. You can define your own user type if you like but the following definitions force your implementation to implement IUser:

public class UserStore<TUser> : IUserLoginStore<TUser>, IUserClaimStore<TUser>, IUserRoleStore<TUser>, IUserPasswordStore<TUser>, IUserSecurityStampStore<TUser>, IUserStore<TUser>, IDisposable where TUser : global::Microsoft.AspNet.Identity.EntityFramework.IdentityUser public class UserManager<TUser> : IDisposable where TUser : global::Microsoft.AspNet.Identity.IUser

I think it’s fine to have that constraint as IUser is an abstraction with minimal content:

string Id { get; }

string UserName { get; set; }

IdentityDbContext also provides the mapping between the entity classes and their DB representations. It also ensures that the tables are properly created when they are needed for the first time.

In summary we can say the Microsoft.AspNet.Identity.EntityFramework library provides the EntityFramework implementation of the abstractions in the Microsoft.AspNet.Identity.Core library. Let’s look at the concrete classes in some more detail.

First go at customisation

We’ve discussed the UserManager in some detail in the previous and this post. The Login action is represented by two methods in AccountController.cs:

[AllowAnonymous] public ActionResult Login(string returnUrl) [HttpPost] [AllowAnonymous] [ValidateAntiForgeryToken] public async Task<ActionResult> Login(LoginViewModel model, string returnUrl)

The GET action method on top is fired when the user navigates to the Login page with the login form. The upon pressing the Log in button the POST action is invoked which accepts the LoginViewModel which in turn has 3 properties:

public string UserName { get; set; }

public string Password { get; set; }

public bool RememberMe { get; set; }

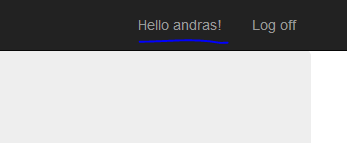

You’ll see that these are populated from the form. The POST Login method is the more interesting one as far as Identity is concerned. In the body of the method the UserManager will try to find the ApplicationUser with the FindAsync method. If the user exists, i.e. it is not null, then she is signed in and redirected to the return url. Otherwise the ModelState is invalidated.

Let’s see how we can add our custom property to the ApplicationUser object. Locate the object and add the following property:

public class ApplicationUser : IdentityUser

{

public string FavouriteProgrammingLanguage { get; set; }

}

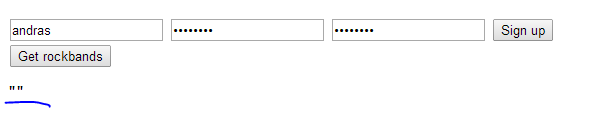

We’ll need to extend the corresponding view model if we want to collect this information from the user. Locate RegisterViewModel in Models/AccountViewModel.cs. It will have 3 fields: username, password and confirm password. Add a 4th one:

[Required]

[Display(Name="Favourite programming language")]

[DataType(DataType.Text)]

public string FavouriteProgrammingLanguage { get; set; }

Next open Register.cshtml in the Views/Account folder. You’ll see a form-group div where the user has to confirm the password. Just underneath add a new div:

<div class="form-group">

@Html.LabelFor(m => m.FavouriteProgrammingLanguage, new { @class = "col-md-2 control-label" })

<div class="col-md-10">

@Html.TextBoxFor(m => m.FavouriteProgrammingLanguage, new { @class = "form-control" })

</div>

</div>

Back in AccountController.cs locate the POST Register method that accepts a RegisterViewModel object. You’ll see the following bit of code after the if statement:

var user = new ApplicationUser() { UserName = model.UserName };

Extend the object as follows:

var user = new ApplicationUser() { UserName = model.UserName, FavouriteProgrammingLanguage = model.FavouriteProgrammingLanguage };

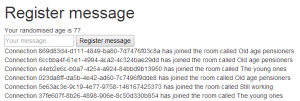

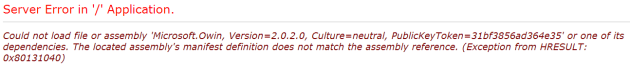

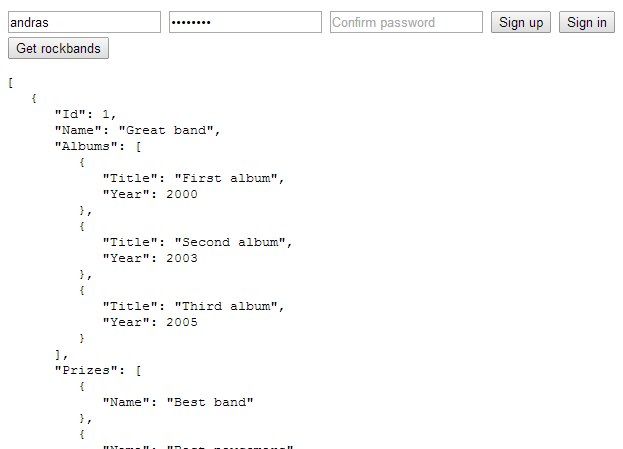

Let’s run the app and see what happens. Don’t log in with the user you created before. Instead, click on the Register link. The Register page should show the new text field. Create a new user, provide a programming language and press the Register button and.. …the yellow screen of death appears:

We’ve changed the entity structure but the database isn’t recreated for us on the fly of course. We’ll rectify this problem in the next post which will discuss DB migrations with EF in the User data context. We’ll revisit migrations in a greater detail in a planned series on EntityFramework which will follow this series.

The new field needs to be included elsewhere like on the Manage.cshtml view for completeness, but you can do that as an exercise.

Read the next post in this series here.

You can view the list of posts on Security and Cryptography here.