Introduction

This post builds upon the basics of RabbitMQ in .NET. If you are new to this topic you should check out all the previous posts listed on this page. I won’t provide any details on bits of code that we’ve gone through before.

Most of the posts on RabbitMQ on this blog are based on the work of RabbitMQ guru Michael Stephenson.

Messaging systems that handle very large amounts of messages per second are normally designed to take care of small and concise messages. This is logical; it is a lot more efficient to process a small message than a large one.

RabbitMQ can handle large messages with 2 different techniques:

- Chunking: the large message is chunked into smaller units by the Sender and reassembled by the Receiver

- Buffering: the message is buffered and sent in one piece

However, note that handling large messages means a negative impact on performance depending on the storage mechanism of the message: in memory – not persistent – or on disk – persistent.

Despite the general recommendation for small messages there may be occasions where you simply have to deal with large ones. A typical example is when you need to send the contents of a file.

A strategy you may follow is to have a special dedicated server with a RabbitMQ instance installed which is designated to handle large messages. “Normal” short messages are then handled by the main RabbitMQ instances.

There’s no magic built-in method in the RabbitMq library to handle chunking and buffering, we’ll have to write some code to make them work. Don’t worry, it just simple standard .NET File I/O.

Buffered message demo

If you’ve gone through the other posts on RabbitMQ on this blog then you’ll have a Visual Studio solution ready to be extended. Otherwise just create a new blank solution in Visual Studio 2012 or 2013. Add a new solution folder called LargeMessages to the solution. In that solution add the following projects:

- A console app called LargeMessageReceiver

- A console app called LargeMessageSender

- A C# library called MessagingService

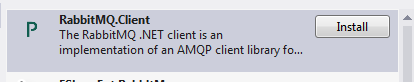

Add the following NuGet package to all three projects:

Add a project reference to MessagingService from LargeMessageReceiver and LargeMessageSender. Add a class called RabbitMqService to MessagingService with the following code:

public class RabbitMqService

{

private string _hostName = "localhost";

private string _userName = "guest";

private string _password = "guest";

public static string LargeMessageBufferedQueue = "LargeMessageBufferedQueue";

public IConnection GetRabbitMqConnection()

{

ConnectionFactory connectionFactory = new ConnectionFactory();

connectionFactory.HostName = _hostName;

connectionFactory.UserName = _userName;

connectionFactory.Password = _password;

return connectionFactory.CreateConnection();

}

}

Let’s set up the queue. Add the following code to Main of LargeMessageSender:

RabbitMqService rabbitMqService = new RabbitMqService();

IConnection connection = rabbitMqService.GetRabbitMqConnection();

IModel model = connection.CreateModel();

model.QueueDeclare(RabbitMqService.LargeMessageBufferedQueue, true, false, false, null);

Run the Sender project. Check in the RabbitMq management console that the queue has been set up.

Comment out the call to model.QueueDeclare, we won’t need it.

Next get a text file ready that is about 15-18 MB in size. Copy or download some large text from the internet and save it on your hard drive somewhere.

Add the following code in Program.cs of the Sender:

private static void RunBufferedMessageExample(IModel model)

{

string filePath = @"c:\large_file.txt";

ConsoleKeyInfo keyInfo = Console.ReadKey();

while (true)

{

if (keyInfo.Key == ConsoleKey.Enter)

{

IBasicProperties basicProperties = model.CreateBasicProperties();

basicProperties.SetPersistent(true);

byte[] fileContents = File.ReadAllBytes(filePath);

model.BasicPublish("", RabbitMqService.LargeMessageBufferedQueue, basicProperties, fileContents);

}

keyInfo = Console.ReadKey();

}

}

So when we press Enter then the large file is read into a byte array. The byte array is then sent to the queue we’ve just set up. Insert a call to this method from Main.

Now let’s turn to the Receiver. Add the following code to Main in Program.cs of LargeMessageReceiver:

RabbitMqService commonService = new RabbitMqService();

IConnection connection = commonService.GetRabbitMqConnection();

IModel model = connection.CreateModel();

ReceiveBufferedMessages(model);

…where ReceiveBufferedMessages looks as follows:

private static void ReceiveBufferedMessages(IModel model)

{

model.BasicQos(0, 1, false);

QueueingBasicConsumer consumer = new QueueingBasicConsumer(model);

model.BasicConsume(RabbitMqService.LargeMessageBufferedQueue, false, consumer);

while (true)

{

BasicDeliverEventArgs deliveryArguments = consumer.Queue.Dequeue() as BasicDeliverEventArgs;

byte[] messageContents = deliveryArguments.Body;

string randomFileName = string.Concat(@"c:\large_file_from_rabbit_", Guid.NewGuid(), ".txt");

Console.WriteLine("Received message, will save it to {0}", randomFileName);

File.WriteAllBytes(randomFileName, messageContents);

model.BasicAck(deliveryArguments.DeliveryTag, false);

}

}

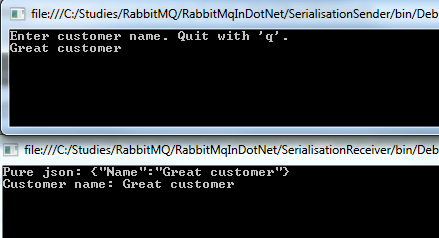

Run the Sender application. Next, start the Receiver as well: right-click on it in VS, select Debug, Start new instance. There should be 2 console windows up and running. Have the Sender as active and press Enter. The file should be read and sent over to the receiver and saved under the random file name:

Chunked messages

Let’s set up a different queue for this demo. Add the following static string to RabbitMqService:

public static string ChunkedMessageBufferedQueue = "ChunkedMessageBufferedQueue";

We’ll reorganise the code a bit in Main of LargeMessageSender.Program.cs:

static void Main(string[] args)

{

RabbitMqService rabbitMqService = new RabbitMqService();

IConnection connection = rabbitMqService.GetRabbitMqConnection();

IModel model = connection.CreateModel();

//model.QueueDeclare(RabbitMqService.LargeMessageBufferedQueue, true, false, false, null);

//RunBufferedMessageExample(model);

model.QueueDeclare(RabbitMqService.ChunkedMessageBufferedQueue, true, false, false, null);

}

Run the Sender to create the queue. Check in the RabbitMq management console that it was in fact created. Comment out the call to model.QueueDeclare. Add the following private method to Program.cs of LargeMessageSender:

private static void RunChunkedMessageExample(IModel model)

{

string filePath = @"c:\large_file.txt";

int chunkSize = 4096;

while (true)

{

ConsoleKeyInfo keyInfo = Console.ReadKey();

if (keyInfo.Key == ConsoleKey.Enter)

{

Console.WriteLine("Starting file read operation...");

FileStream fileStream = File.OpenRead(filePath);

StreamReader streamReader = new StreamReader(fileStream);

int remainingFileSize = Convert.ToInt32(fileStream.Length);

int totalFileSize = Convert.ToInt32(fileStream.Length);

bool finished = false;

string randomFileName = string.Concat("large_chunked_file_", Guid.NewGuid(), ".txt");

byte[] buffer;

while (true)

{

if (remainingFileSize <= 0) break;

int read = 0;

if (remainingFileSize > chunkSize)

{

buffer = new byte[chunkSize];

read = fileStream.Read(buffer, 0, chunkSize);

}

else

{

buffer = new byte[remainingFileSize];

read = fileStream.Read(buffer, 0, remainingFileSize);

finished = true;

}

IBasicProperties basicProperties = model.CreateBasicProperties();

basicProperties.SetPersistent(true);

basicProperties.Headers = new Dictionary<string, object>();

basicProperties.Headers.Add("output-file", randomFileName);

basicProperties.Headers.Add("finished", finished);

model.BasicPublish("", RabbitMqService.ChunkedMessageBufferedQueue, basicProperties, buffer);

remainingFileSize -= read;

}

Console.WriteLine("Chunks complete.");

}

}

}

That’s a bit longer than what we normally have. We define a chunk size of 4KB. Then upon pressing enter we start reading the file. We read chunks of 4kb into the variable called ‘buffer’. In the inner while loop we keep reading the file until all bytes have been processed. Upon each iteration we send some metadata about the message in the Headers section: the file name that the receiver can start saving the data into and whether there’s any more message to be expected. We then publish the partial message. Add a call to this method from Main.

Now let’s turn to the Receiver. Re-organise the current code in Main as follows:

static void Main(string[] args)

{

RabbitMqService commonService = new RabbitMqService();

IConnection connection = commonService.GetRabbitMqConnection();

IModel model = connection.CreateModel();

//ReceiveBufferedMessages(model);

ReceiveChunkedMessages(model);

}

…where ReceiveChunkedMessages looks as follows:

private static void ReceiveChunkedMessages(IModel model)

{

model.BasicQos(0, 1, false);

QueueingBasicConsumer consumer = new QueueingBasicConsumer(model);

model.BasicConsume(RabbitMqService.ChunkedMessageBufferedQueue, false, consumer);

while (true)

{

BasicDeliverEventArgs deliveryArguments = consumer.Queue.Dequeue() as BasicDeliverEventArgs;

Console.WriteLine("Received a chunk!");

IDictionary<string, object> headers = deliveryArguments.BasicProperties.Headers;

string randomFileName = Encoding.UTF8.GetString((headers["output-file"] as byte[]));

bool isLastChunk = Convert.ToBoolean(headers["finished"]);

string localFileName = string.Concat(@"c:\", randomFileName);

using (FileStream fileStream = new FileStream(localFileName, FileMode.Append, FileAccess.Write))

{

fileStream.Write(deliveryArguments.Body, 0, deliveryArguments.Body.Length);

fileStream.Flush();

}

Console.WriteLine("Chunk saved. Finished? {0}", isLastChunk);

model.BasicAck(deliveryArguments.DeliveryTag, false);

}

}

Most of this is standard RabbitMq code from previous posts. The new things are that the we read the headers and save the contents of the message body in a file on the C drive.

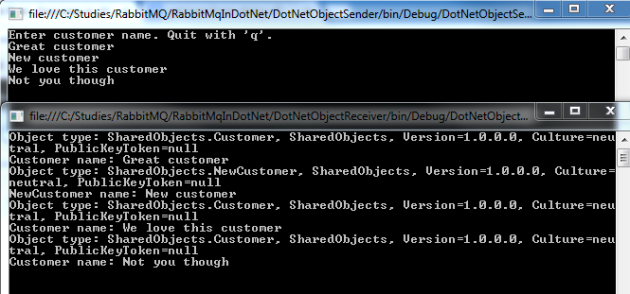

Run the Sender application. Then run the Receiver the same way as in the previous demo. You’ll have two console windows up and running. Make sure that the Sender is selected and press Enter. You’ll see that the chunks are sent over to the Receiver and are processed accordingly:

Check the target file destination to see if the file has been saved.

With the chunking pattern it’s probably a good idea to keep your infrastructure as simple as possible:

- Start with a single Receiver: you can have multiple receivers as we saw int the post on worker queues but then you’ll face the challenge of putting the chunks into the right order

- Have a dedicated queue for chunked messages: multi-purpose queues are cumbersome as we saw [here], you shouldn’t add chunking to the complexity if you can avoid that

Read the next part in this series here.

View the list of posts on Messaging here.