Introduction

We’re now ready to build the ultimate consumer of the application, the web layer. As we said before this layer can be any type of presentation layer: MVC, a web service interface, WPF, a console app, you name it. The backend design that we’ve built up so far should be flexible enough to support either a relatively simple switch of UI type or the addition of new types. You may want to have several multiple entry points into your business app so it’s good if they can rely on the same foundations. Otherwise you may need to build different apps just to support different presentation methods, which is far from optimal.

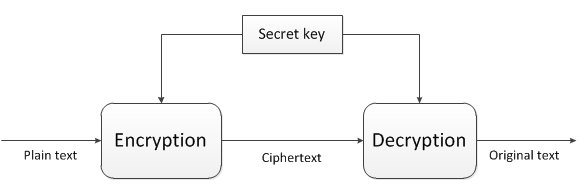

Here we’ll build a web service layer powered by Web API. If you don’t know what it is you can read about it on its official homepage. Here comes a summary:

In short the Web API is a technology by Microsoft to build HTTP-based web services. Web Api uses the standard RESTful way of building a web service with no SOAP overhead; only plain old HTTP messages are exchanged between the client and the server. The client sends a normal HTTP request to a web service with some URI and receives a HTTP response in return.

The technology builds heavily on MVC: it has models and controllers just like a normal MVC web site. It lacks any views of course as a web service provides responses in JSON, XML, plain text etc., not HTML. There are some other important differences:

- The actions in the controllers do not return Action Results: they can return any string based values and HttpResponse objects

- The controllers derive from the ApiController class, not the Controller class as in standard MVC

The routing is somewhat different:

- In standard MS MVC the default routing may look as follows: controller/action/parameters

- In Web API the ‘action’ is omitted by default: Actions will be routed based on the HTTP verb of the incoming HTTP message: GET, POST, PUT, DELETE, HEAD, OPTIONS

- The action method signatures follow this convention: Get(), Get(int id), Post(), Put(), Delete(int id)

- As long as you keep to this basic convention the routing will work without changing the routing in WebApiConfig.cs in the App_Start folder

Routing example: say that the client wants to get data on a customer with id 23. They will send a GET request to our web service with the following URI: http://www.api.com/customers/21. The Web API routing engine will translate this into a Get(int id) method within the controller called CustomersController. If however they want to delete this customer then he will send a DELETE request to the same URI and the routing engine will try to find a Delete(int id) method in CustomersController.

In other words: the supported HTTP verbs have a corresponding method in the correct controller. If a resource does not support a specific verb, e.g. a Customer cannot be deleted, then just omit the Delete(int id) method in the CustomersController and Web API will return a HTTP exception message saying that there’s no suitable method.

The basic convention allows some freedom of naming your action methods. Get, Post etc. can be named Get[resource], Post[resource], e.g. GetCustomer, PostCustomer, DeleteCustomer and the routing will still work. If for any reason you don’t like the default naming conventions you can still use the standard HttpGet, HttpPost type of attributes known from MS MVC.

I won’t concentrate on the details of Web API in this post. If there’s something you don’t understand along the way then make sure to check out the link provided above.

We’ll also see how the different dependencies can be injected into the services, repositories and other items that are dependent upon abstractions. So far we have diligently given room for injecting dependencies according to the letter ‘D‘ in SOLID, like here:

public CustomerService(ICustomerRepository customerRepository, IUnitOfWork unitOfWork)

However, at some point we’ll need to inject these dependencies, right? We could follow poor man’s DI by constructing a new CustomerRepository and a new InMemoryUnitOfWork object as they implement the necessary ICustomerRepository and IUnitOfWork interfaces. However, modern applications use one of the many available Inversion-of-Control containers to take care of these plumbing tasks. In our case we’ll use StructureMap which is quite common to and works very well with .NET projects. IoCs can be difficult to grasp at first as they seem to do a lot of magic, but don’t worry much about them. StructureMap can do a lot for you without having to dig deep into the details on how it works as it’s easy to install and get started with using NuGet.

The web layer

Add a new Web API project by taking the following steps.

1. Add new project

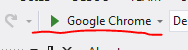

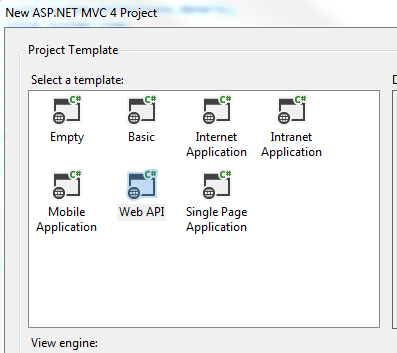

2. Select Web/MVC 4 web application:

Call it DDDSkeletonNET.Portal.WebService.

3. Select Web API in the Project template:

The result is actually a mix between an MVC and a Web API project. Take a look into the Controllers folder. It includes a HomeController which derives from the MVC Controller class and a ValuesController which derives from the Web API ApiController. The project also includes images, views and routing related to MVC. The idea is that MVC views can also consume Web API controllers. Ajax calls can also be directed towards Web API controllers. However, our goal is to have a pure web service layer so let’s clean this up a little:

- Delete the Content folder

- Delete the Images folder

- Delete the Views folder

- Delete the Scripts folder

- Delete both controllers from the Controllers folder

- Delete favicon.ico

- Delete BundleConfig.cs from the App_Start folder

- Delete RouteConfig.cs from the App_Start folder

- Delete the Models folder

- Delete the Areas folder

- In WebApiConfig.Register locate the routeTemplate parameter. It says “api/…” by default. Remove the “api/” bit so that it says {controller}/{id}

- Locate Global.asax.cs. It is trying to call RouteConfig and BundleConfig – remove those calls

The WebService layer should be very slim at this point with only a handful of folders and files. Right-click the Controllers folder and add a new empty API controller called CustomersController:

We’ll need to have an ICustomerService object in the CustomersController so add a reference to the ApplicationServices layer.

Add the following private backing field and constructor to CustomersController:

private readonly ICustomerService _customerService;

public CustomersController(ICustomerService customerService)

{

if (customerService == null) throw new ArgumentNullException("CustomerService in CustomersController");

_customerService = customerService;

}

We’ll want to return Http messages only. Http responses are represented by the HttpResponseMessage object. As all our contoller methods will return a HttpResponseMessage we can assign an extension method to build these messages. Insert a folder called Helpers in the web layer. Add the following extension method to it:

public static class HttpResponseBuilder

{

public static HttpResponseMessage BuildResponse(this HttpRequestMessage requestMessage, ServiceResponseBase baseResponse)

{

HttpStatusCode statusCode = HttpStatusCode.OK;

if (baseResponse.Exception != null)

{

statusCode = baseResponse.Exception.ConvertToHttpStatusCode();

HttpResponseMessage message = new HttpResponseMessage(statusCode);

message.Content = new StringContent(baseResponse.Exception.Message);

throw new HttpResponseException(message);

}

return requestMessage.CreateResponse<ServiceResponseBase>(statusCode, baseResponse);

}

}

We’re extending the HttpRequestMessage object which represents the http request coming to our web service. We build a response based on the Response we received from the service layer. We assume that the http status is OK (200) but if there’s been any exception then we adjust that status and throw a HttpResponseException exception. Make sure to set the namespace to DDDSkeletonNET.Portal so that the extension is visible anywhere in the project without having to add using statements.

ConvertToHttpStatusCode() is also an extension method. Add another class called ExceptionDictionary to the Helpers folder:

public static class ExceptionDictionary

{

public static HttpStatusCode ConvertToHttpStatusCode(this Exception exception)

{

Dictionary<Type, HttpStatusCode> dict = GetExceptionDictionary();

if (dict.ContainsKey(exception.GetType()))

{

return dict[exception.GetType()];

}

return dict[typeof(Exception)];

}

private static Dictionary<Type, HttpStatusCode> GetExceptionDictionary()

{

Dictionary<Type, HttpStatusCode> dict = new Dictionary<Type, HttpStatusCode>();

dict[typeof(ResourceNotFoundException)] = HttpStatusCode.NotFound;

dict[typeof(Exception)] = HttpStatusCode.InternalServerError;

return dict;

}

}

Here we maintain a dictionary of Exception/HttpStatusCode pairs. It would be nicer of course to read this directly from the Exception object possibly through an Adapter but this solution is OK for now.

Let’s implement the get-all-customers method in CustomersController. So we’ll need a Get method without any parameters that corresponds to the /customers route. That should be as easy as the following:

public HttpResponseMessage Get()

{

ServiceResponseBase resp = _customerService.GetAllCustomers();

return Request.BuildResponse(resp);

}

We ask the service to retrieve all customers and convert that response into a HttpResponseMessage object.

We cannot yet use this controller as ICustomerService is null, there’s no concrete type behind it yet within the controller. This is where StructureMap enters the scene. Open the Manage NuGet Packages window and install the following package:

The installer adds a couple of new files to the web service layer:

- 3 files in the DependencyResolution folder

- StructuremapMvc.cs in the App_Start folder

The only file we’ll consider in any detail is IoC.cs in the DependencyResolution folder. Don’t worry about the rest, they are not important to our main discussion. Here’s a short summary:

StructuremapMvc was auto-generated by the StructureMap NuGet package and it can safely be ignored, it simply works.

DependencyResolution folder: IoC.cs is important to understand, the other auto-generated classes can be ignored. In IoC.cs we declare which concrete types we want StructureMap to inject in place of the abstractions. If you are not familiar with IoC containers then you may wonder how ICustomerService is injected in CustomerController and how ICustomerRepository is injected in CustomerService. This is achieved automagically through StructureMap and IoC.cs is where we instruct it where to look for concrete types and in special cases tell it explicitly which concrete type to take.

StructureMap follows a simple built-in naming convention: if it encounters an interface starting with an ‘I’ it will look for a concrete type with the same name without the ‘I’ in front. Example: if it sees that an ICustomerService interface is needed then it will try to fetch a CustomerService object. This is expressed by the scan.WithDefaultConventions() call. It is easy to register new naming conventions for StructureMap if necessary – let me know in the comment section if you need any code sample.

We also need to tell StructureMap where to look for concrete types. It won’t automatically find the implementations of our abstractions, we need to give it some hints. We can declare this in the calls to scan.AssemblyContainingType of type T. Example: scan.AssemblyContainingType() of type CustomerRepository means that StructureMap should go and look in the assembly which contains the CustomerRepository object. Note that this does not mean that CustomerRepository must be injected at all times. It simply says that StructureMap will look in that assembly for concrete implementations of an abstraction. I could have picked any object from that assembly, it doesn’t matter. So these calls tell StructureMap to look in each assembly that belong to the same solution.

There are cases where the standard naming convention is not enough. Then you can explicitly tell StructureMap which concrete type to inject. Example: x.For()[abstraction].Use()[implementation]; means that if StructureMap sees a dependency on ‘abstraction’ then it should inject a new ‘implementation’ type.

ObjectFactory.AssertConfigurationIsValid() will make sure that an exception is thrown during project start-up if StructureMap sees a dependency for which it cannot find any suitable implementation.

Update the Initialize() method in IoC.cs to the following:

public static IContainer Initialize()

{

ObjectFactory.Initialize(x =>

{

x.Scan(scan =>

{

scan.TheCallingAssembly();

scan.AssemblyContainingType<ICustomerRepository>();

scan.AssemblyContainingType<CustomerRepository>();

scan.AssemblyContainingType<ICustomerService>();

scan.AssemblyContainingType<BusinessRule>();

scan.WithDefaultConventions();

});

x.For<IUnitOfWork>().Use<InMemoryUnitOfWork>();

x.For<IObjectContextFactory>().Use<LazySingletonObjectContextFactory>();

});

ObjectFactory.AssertConfigurationIsValid();

return ObjectFactory.Container;

}

You’ll need to reference all other layers from the Web layer for this to work. We’re telling StructureMap to scan all other assemblies by declaring all types that are contained in those assemblies – again, I could have picked ANY type from the other projects, so don’t get hung up on questions like “Why did he choose BusinessRule?”. These calls will make sure that the correct implementations will be found based on the default naming convention mentioned above. There are two cases where this convention is not enough: IUnitOfWork and IObjectContextFactory. Here we use the For and Use extension methods to declare exactly what we need. Finally we want to assert that all implementations have been found. You can test it for yourself: comment out the line on IUnitOfWork, start the application – make sure to set the web layer as the startup project – and you should get a long exception message, here’s the gist of it:

StructureMap.Exceptions.StructureMapConfigurationException was unhandled by user code

No Default Instance defined for PluginFamily DDDSkeletonNET.Infrastructure.Common.UnitOfWork.IUnitOfWork

StructureMap couldn’t resolve the IUnitOfWork dependency so it threw an error.

Open the properties window of the web project and specify the route to customers:

Set a breakpoint at this line in CustomersController:

ServiceResponseBase resp = _customerService.GetAllCustomers();

…and press F5. Execution should stop at the break point. Hover over _customerService with the mouse to check the status of the dependency. You’ll see it is not null, so StructureMap has correctly found and constructed a CustomerService object for us. Step through the code with F11 to see how it is all connected. You’ll see that all dependencies have been resolved correctly.

However, at the end of the loop, when the 3 customers that were retrieved from memory should be presented, we get the following exception:

The ‘ObjectContent`1’ type failed to serialize the response body for content type ‘application/xml; charset=utf-8’.

Open WebApiConfig and add the following lines of code to the Register method:

var json = config.Formatters.JsonFormatter;

json.SerializerSettings.PreserveReferencesHandling = Newtonsoft.Json.PreserveReferencesHandling.Objects;

config.Formatters.Remove(config.Formatters.XmlFormatter);

This will make sure that we return our responses in JSON format.

Re-run the app and you should see some JSON on your browser:

Yaaay, after much hard work we’re getting somewhere at last! How can we retrieve a customer by id? Add the following overloaded Get method to the Customers controller:

public HttpResponseMessage Get(int id)

{

ServiceResponseBase resp = _customerService.GetCustomer(new GetCustomerRequest(id));

return Request.BuildResponse(resp);

}

Run the application and enter the following route in the URL window: customers/1. You should see that the customer with id 1 is returned:

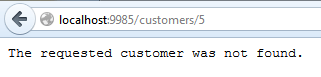

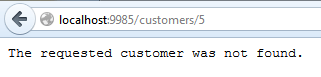

Now try this with an ID that you know does not exist, such as customers/5. An exception will be thrown in the application. Let the execution continue and you should see the following exception message in your web browser:

This is the message we set in the code if you recall.

What if we want to format the data slightly differently? It’s good that we have a customer view model and request-response objects where we are free to change what we want without modifying the corresponding domain object. Open the application services layer and add a reference to the System.Runtime.Serialization library. Modify the CustomerViewModel object as follows:

[DataContract]

public class CustomerViewModel

{

[DataMember(Name="Customer name")]

public string Name { get; set; }

[DataMember(Name="Address")]

public string AddressLine1 { get; set; }

public string AddressLine2 { get; set; }

[DataMember(Name="City")]

public string City { get; set; }

[DataMember(Name="Postal code")]

public string PostalCode { get; set; }

[DataMember(Name="Customer id")]

public int Id { get; set; }

}

Re-run the application and navigate to customers/1. You should see the updated property names:

You can decorate the Response objects as well with these attributes.

This was a little change in the property names only but feel free to add extra formats to the view model, it’s perfectly fine.

We’re missing the insert, update and delete methods. Let’s implement them here and we’ll test them in the next post.

As far as I’ve seen there’s a bit of confusion over how the web methods PUT and POST are supposed to be used in web requests. DELETE is clear, we want to delete a resource. GET is also straightforward. However, PUT and POST are still heavily debated. This post is not the time and place to decide once and for all what their roles are, so I’ll take the following approach:

- POST: insert a resource

- PUT: update a resource

Here come the implementations:

public HttpResponseMessage Post(CustomerPropertiesViewModel insertCustomerViewModel)

{

InsertCustomerResponse insertCustomerResponse = _customerService.InsertCustomer(new InsertCustomerRequest() { CustomerProperties = insertCustomerViewModel });

return Request.BuildResponse(insertCustomerResponse);

}

public HttpResponseMessage Put(UpdateCustomerViewModel updateCustomerViewModel)

{

UpdateCustomerRequest req =

new UpdateCustomerRequest(updateCustomerViewModel.Id)

{

CustomerProperties = new CustomerPropertiesViewModel()

{

AddressLine1 = updateCustomerViewModel.AddressLine1

,AddressLine2 = updateCustomerViewModel.AddressLine2

,City = updateCustomerViewModel.City

,Name = updateCustomerViewModel.Name

,PostalCode = updateCustomerViewModel.PostalCode

}

};

UpdateCustomerResponse updateCustomerResponse = _customerService.UpdateCustomer(req);

return Request.BuildResponse(updateCustomerResponse);

}

public HttpResponseMessage Delete(int id)

{

DeleteCustomerResponse deleteCustomerResponse = _customerService.DeleteCustomer(new DeleteCustomerRequest(id));

return Request.BuildResponse(deleteCustomerResponse);

}

…where UpdateCustomerViewModel derives from CustomerPropertiesViewModel:

public class UpdateCustomerViewModel : CustomerPropertiesViewModel

{

public int Id { get; set; }

}

We’ll test these in the next post where we’ll also draw the conclusions of what we have achieved to finish up the series.

View the list of posts on Architecture and Patterns here.