Web farms in .NET and IIS part 1: a general introduction

June 17, 2013 12 Comments

Introduction

In this series I’ll try to give you an overview of web farms in the context of IIS and .NET. The target audience is programmers who want to get started with web farms and the MS technologies built around them. I used IIS 7.5 and .NET4.5 in all demos but you should be fine with IIS7.0 and .NET4.0 as well and things should not be too different in IIS8.0 either.

What is a web farm?

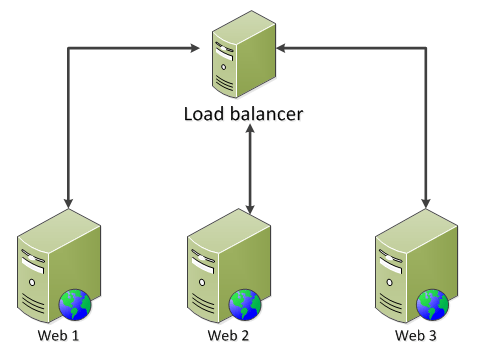

A web farm is when you have two servers that perform the same service. You make an exact copy of an existing web server and put a load balancer in front of them like this:

It is the load balancer that catches all web requests to your domain and distributes them among the available servers based on their current load.

The above structure depicts the web farm configuration type called Local Content. In this scenario each web farm machine keeps the content locally. It is up to you or your system administrator to deploy the web site to each node after all the necessary tests have been passed. If the web site writes to a local file then the contents of that file should be propagated immediately to every node in the web farm.

With Local Content the servers are completely isolated. If something goes wrong with one of them then the system can continue to function with the other servers up and running. This setup is especially well suited for distributing the load evenly across the servers.

Disadvantages include the need for an automated content replication across servers which may become quite complicated if you have many elements to replicate: web content, certificates, COM+ objects, GAC, registry entries etc. Also, as mentioned above, if the web site writes to disk then the contents of that file must be propagated to the other nodes immediately. You can alternatively have a file share but that introduces a single point of failure so make sure it is redundant.

Local Content is probably the most common solution for many high traffic websites on the Internet today. There are other options though:

- Shared network content, which uses a central location to manage the content where all web servers in the farm point to that location

- Shared Storage Area Network (SAN) or Storage Spaces in Windows Server 2012, which allow the storage space to be attached as a local volume so that it can be mounted as a drive or a folder on the system

We’ll concentrate on the Local Content option as it is the easiest to get started with and it suits most web farm scenarios out there. If you’re planning to build the next Google or Facebook then your requirements are way beyond the scope of this post anyway: take a look at the web farming frameworks by Microsoft mentioned at the very end of this post. They are most suitable for large websites, especially Windows Azure Services.

Why use a web farm?

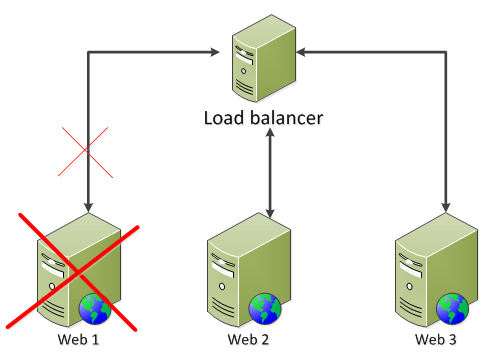

The main advantage is reliability. The load balancer “knows” if one of the web servers is out of service, due to maintenance or a general failure, it doesn’t matter, and makes sure that no web request is routed to that particular server. If you need to patch one of the servers in the farm you can simply temporarily remove it from the farm, perform the update and then bring the server up again:

You can even deploy your web deployment package on each server one after the other and still maintain a continuous service to your customers.

The second main advantage of a web farm is to be able to scale up the web tier. In case you have a single web server and you notice that it cannot handle the amount of web traffic you can copy the server so that the load will be spread out by the load balancer. The servers don’t have to be powerful machines with a lot of CPU and RAM. This is called scaling out.

By contrast scaling out the data tier, i.e. the database server has been a lot more difficult. There are available technologies today that make this possible, such as NoSql databases. However, the traditional solution to increase the responsiveness of the data tier has been to scale up – note ‘up’, not ‘out’ – which means adding more capacity to the machine serving as the data tier: more RAM, more CPU, bigger servers. This approach is more expensive than buying more smaller web machines, so scaling out has an advantage in terms of cost effectiveness:

Load balancers

How do load balancers distribute the web traffic? There are several algorithms:

- Round-robin: each request is assigned to the next server in the list, one server after the other. This is also called the poor man’s load balancer as this is not true load balancing. Web traffic is not distributed according to the actual load of each server.

- Weight-based: each server is given a weight and requests are assigned to the servers according to their weight. Can be an option if your web servers are not of equal quality and you want to direct more traffic to the stronger ones.

- Random: the server to handle the request is randomly selected

- Sticky sessions: the load balancer keeps track of the sessions and ensures that return visits within the session always return to the same server

- Least current request: route traffic to the server that currently has the least amount of requests

- Response time: route traffic to the web server with the shortest response time

- User or URL information: some load balancers offer the ability to distribute traffic based on the URL or the user information. Users from one geographic location region may be sent to the server in that location. Requests can be routed based on the URL, the query string, cookies etc.

Apart from algorithms we can group load balancers according to the technology they use:

- Reverse Proxy: a reverse proxy takes an incoming request and makes another request on behalf of the user. We say that the Reverse Proxy server is a middle-man or a man-in-the-middle in between the web server and the client. The load balancer maintains two separate TCP connections: one with the user and one with the web server. This option requires only minimal changes to your network architecture. The load balancer has full access to the all the traffic on the way through allowing it to check for any attacks and to manipulate the URL or header information. The downside is that as the reverse proxy server maintains the connection with the client you may need to set a long time-out to prepare for long sessions, e.g. in case of a large file download. This opens the possibility for DoS attacks. Also, the web servers will see the load balancer server as the client. Thus any logic that is based on headers like REMOTE_ADDR or REMOTE_HOST will see the IP of the proxy server rather than the original client. There are software solutions out there that rewrite the server variables and fool the web servers into thinking that they had a direct line with the client.

- Transparent Reverse Proxy: similar to Reverse Proxy except that the TCP connection between the load balancer and the web server is set with the client IP as the source IP so the web server will think that the request came directly from the client. In this scenario the web servers must use the load balancer as their default gateway.

- Direct Server Return (DSR): this solution runs under different names such as nPath routing, 1 arm LB, Direct Routing, or SwitchBack. This method forwards the web request by setting the web server’s MAC address. The result is that the web server responds directly back to the client. This method is very fast which is also its main advantage. As the web response doesn’t go through the load balancer, even less capable load balancing solutions can handle a relatively large amount of web requests. However, this solution doesn’t offer some of the great options of other load balancers, such as SSL offloading – more on that later

- NAT load balancing: NAT, which stands for Network Address Translation, works by changing the destination IP address of the packets

- Microsoft Network Load Balancing: NLB manipulates the MAC address of the network adapters. The servers talk among themselves to decide which one of them will respond to the request. The next blog post is dedicated to NLB.

Let’s pick 3 types of load balancers and the features available to them:

- Physical load balancers that sit in front of the web farm, also called Hardware

- ARR: Application Request Routing which is an extension to IIS that can be placed in front of the web tier or directly on the web tier

- NLB: Network Load Balancing which is built into Windows Server and performs some basic load balancing behaviour

No additional failure points:

This point means whether the loadbalancing solution introduces any additional failure points in the overall network.

Physical machines are placed in front of your web farm and they can of course fail. You can put a multiple of these to minimise the possibility of a failure but we still have this possible failure point.

With ARR you can put the load balancer in front of your web farm on a separate machine or a web farm of load balancers or on the same web tier as the web servers. If it’s on a separate tier then it has some additional load balancing features. Putting it on the same tier adds complexity to the configuration but eliminates additional failure points, hence the -X sign in the appropriate cell.

NLB runs on the web server itself so there are no additional failure points.

Health checks

This feature means whether the load balancer can check whether the web server is healthy. This usually means a check where we instruct the load balancer to periodically send a request to the web servers and expect some type of response: either a full HTML page or just a HTTP 200.

NLB is only solution that does not have this feature. NLB will route traffic to any web server and will be oblivious of the answer: can be a HTTP 500 or even no answer at all.

Caching

This feature means the caching of static – or at least relatively static – elements on your web pages, such as CSS or JS, or even entire HTML pages. The effect is that the load balancer does not have to contact the web servers for that type of content which decreases the response times.

NLB does not have this feature. If you put ARR on your web tier then this feature is not available really as it will be your web servers that perform caching.

SSL offload

SSL Offload means that the load balancer will take over the SSL encryption-decryption process from the web servers which also adds to the overall efficiency. SSL is fairly expensive from a CPU perspective so it’s nice to relieve the web machine of that responsibility and hand it over to the probably lot more powerful load balancer.

NLB doesn’t have this feature. Also, if you put ARR on your web tier then this feature is not available really as it will be your web servers that perform SSL encryption and decryption.

A benefit of this feature is that you only have to install the certificate on the load balancer. Otherwise you must make sure to replicate the SSL certificate(s) on every node of the web farm.

If you go down this path then make sure to go through the SSL issuing process on one of the web farm servers – create a Certificate Signing Request (CSR) and send it to a certificate authority (CA). The certificate that the CA generates will only work on the server where the CSR was generated. Install the certificate on the web farm server where you initiated the process and then you can export it to the other servers. The CSR can only be used on one server but an exported certificate can be used on multiple servers.

There’s a new feature in IIS8 called Central Certificate Store which lets you synchronise your certificates across multiple servers.

Geo location

Physical loadbalancers and ARR provide some geolocation features. You can employ many load balancers throughout the world to be close to your customers or have your load balancer point to different geographically distributed data centers. In reality you’re better off looking at cloud based solutions or CDNs such as Akamai, Windows Azure or Amazon.

Low upfront cost

Hardware load balancers are very expensive. ARR and NLB are for free meaning that you don’t have to pay anything extra as they are built-in features of Windows Server and IIS. You probably want to put ARR on a separate machine so that will involve some extra cost but nowhere near what hardware loadbalancers will cost you.

Non-HTTP traffic

Hardware LBs and NLB can handle non-HTTP traffic whereas ARR is a completely HTTP based solution. So if you’re looking into possibilities to distribute other types of traffic such as for SMTP based mail servers then ARR is not an option.

Sticky sessions

This feature means that if a client returns for a second request then the load balancer will redirect that traffic to the same web server. It is also called client affinity. This can be important for web servers that store session state locally so that when the same visitor comes back then we don’t want the state relevant to that user to be unavailable because the request was routed to a different web server.

Hardware LBs and ARR provide a lot of options to introduce sticky sessions including cookie-based solutions. NLB can only perform IP-based sticky sessions, it doesn’t know about cookies and HTTP traffic.

Your target should be to avoid sticky sessions and solve your session management in a different way – more on state management in a future post. If you have sticky sessions then the load balancer is forced to direct traffic to a certain server irrespective of its actual load, thus beating the purpose of load distribution. Also, if the server that received the first request becomes unavailable then the user will lose all session data and may receive an exception or unexpected default values in place of the values saved in the session variables.

Other types of load balancers

Software

With software load balancers you can provide your own hardware while using the vendor-supported software for load balancing. The advantage is that you can provide your own hardware to meet your load balancing needs which can save you a lot of money.

We will in a later post look at Application Request Routing (ARR) which is Microsoft’s own software based reverse proxy load balancer which is a plug-in to IIS.

Another solution is HAProxy but it doesn’t run on Windows.

A commercial solution that runs on Windows is KEMP LoadMaster by KEMP Technologies.

Frameworks

There are frameworks that unite load balancers and other functionality together into a cohesive set of functions. Web Farm Framework and Windows Azure Services are both frameworks provided by Microsoft that provide additional functionality on top of load balancing. We’ll look at WFF in a later post in more depth.