Web farms in .NET and IIS part 4: Code deployment

June 27, 2013 2 Comments

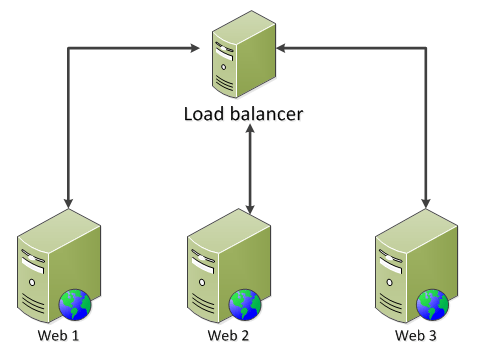

So now we have our web farm in place where the servers in the cluster are identical machines: they have the same CPU, same RAM, same OS etc. This is an important point as you certainly want to provide the same user experience regardless of which web farm server receives the web request.

A good way to ensure this is through using templates in a virtualisation environment, such as VMWare. You define a template for a model machine with all the necessary physical traits such as the CPU, disk size, RAM etc. You then use this template to create new virtual machines. This process is a lot smoother and cheaper then buying new physical machines.

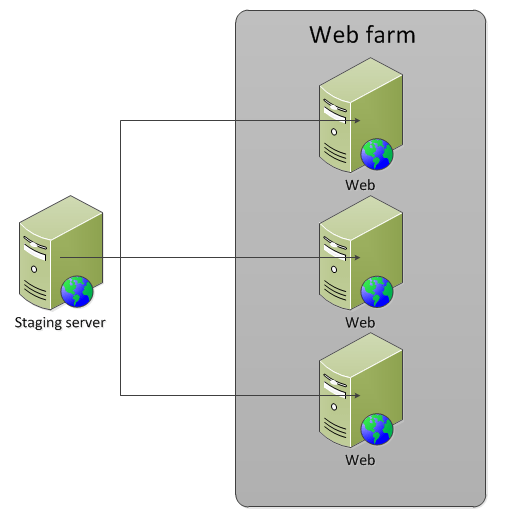

The next step is code deployment. You typically want to deploy your website on all machines in the farm, right? You can of course manually copy over your deployment package to each and every server one by one but that’s inefficient and tedious. A staging server can help you out.

Staging server

A staging server is not part of the web farm therefore it won’t get any web requests. However, it will also have IIS installed just like the machines in the web farm. We can first deploy our code to that IIS and we can use that IIS to deploy the website to the web farm servers. The staging server can act as an environment where we check if our code is working properly, if the configuration is working fine etc. It is the last stage before actual employment so ideally the staging server has the same physical properties – CPU, RAM, etc. – as the servers in the web farm:

There’s a free tool from Microsoft that you can use to deploy your code: MSDeploy, or Web Deploy. MSDeploy is a command line tool that Visual Studio uses behind the scenes if you choose that deployment method when publishing your code. It can be used to migrate IIS configuration, web content, Windows components. It is a powerful tool which is well suited for web farms because it allows to synchronise some more difficult items such as the registry or the GAC.

Demo

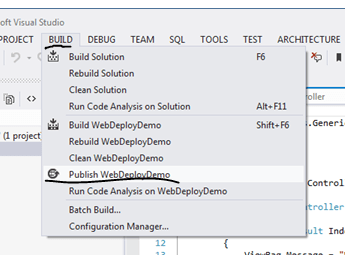

Open Visual Studio 2010 or 2012 and create a new MVC internet application. I will go through the steps using VS 2012 but web deployment is available in VS 2010 as well. You can leave the default website content as it is, we’re only interested in the deployment options. You can open the publish options from the Build menu:

This opens the Public Web window:

In the Select or import a publish profile drop down list select New… Give some meaningful name to the deployment profile:

You can then select the deployment method:

The Web Deploy publish method represents the MSDeploy tool mentioned above. Like in parts 2 and 3 of this series I don’t have access to any private web farm so I’ll just deploy this web site to the IIS instance of my own computer.

UPDATE: in this post I show how to set up Web Deploy with a real external web server.

Open the IIS manager and add a new web site:

Give it some name and select the physical location of the deployment package. You can create a new folder using the Make New Folder button.

Back in VS we can now specify the server as localhost and define the application name which we’ve just set up:

You can validate the connection using the Validate Connection button which requires that you start VS as an administrator.

The Service URL can be the location of your staging server or that of a hosted environment that you’re deploying your site to: http://staging.mysite.com, http://finaltest.mysite.com or whatever URL you gave that IIS website. Press Publish and you may be greeted with the following error message in VS:

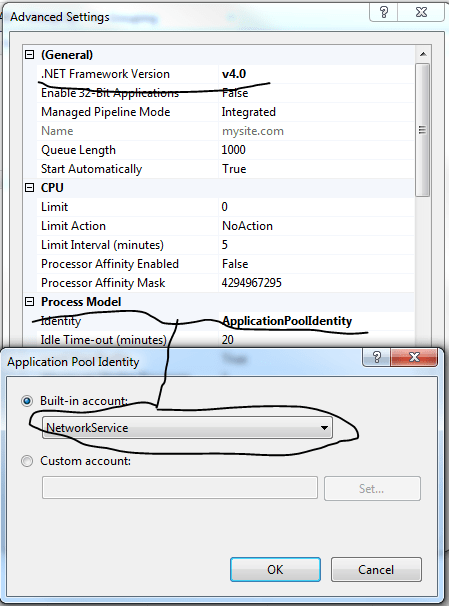

Back in IIS we need to modify the default application pool that IIS created automatically for the new web site:

Right-click that application pool and select Advanced settings from the context menu. Change two things in the Advanced Settings window:

Run the deployment from VS again and it should proceed without errors:

You can even check the contents of the deployment folder you specified in IIS to verify that the web site was in fact deployed:

You can even see the same structure in IIS under the website:

In a real life environment we would check this code into source control, such as GIT or SVN. The staging server would pull out of source control the latest check-in code but for now we’ll just pretend that this localhost environment represents our source control server. So we’ll push this code to our staging server thereby doing what a source control would do for us automatically.

The msdeploy tool is normally located at C:/Program Files/IIS/Microsoft Web Deploy V3. At the time of writing this post V3 was the latest available version. By the time you read this there may be a newer version of course. Open a command prompt, navigate to that directory and run msdeploy.exe without any arguments. You should get a long list of options that msdeploy can be used with:

We can write a short batch file to carry out the necessary msdeploy commands for our deployment purposes. In the batch file, which we can call deploy.bat we first specify the directory:

cd “\Program Files\IIS\Microsoft Web Deploy V3”

Then we can fill up the file with msdeploy commands. To deploy from the current location, i.e. localhost, to our staging environment, we can write like this:

msdeploy -verb:sync -source:iisApp=mysite.com -dest:iisApp=mysite.com,computerName=[name of staging server machine]

We’re instructing msdeploy to pull the code out of mysite.com on the local machine and deploy it to mysite.com on the staging server. This command will simply take the contents of the mysite.com website and push it over to the given destination.

Then from there it’s equally straightforward to deploy to our web farm machines:

msdeploy -verb:sync -source:webServer,computerName=[name of staging server machine] -dest:webServer,computerName=[name of first machine in web farm]

msdeploy -verb:sync -source:webServer,computerName=[name of staging server machine] -dest:webServer,computerName=[name of second machine in web farm]

So here we don’t just copy the application itself but the entire IIS config and its contents from the staging server and push it over to the web servers one by one. We’re taking the staging server and push it out to farm machine 1 and 2.

We do this because we want to make sure that the web farm machines have the exact same IIS configuration as the staging one. Remember that we can run tests on the staging server where we fine-tune some IIS settings, like response headers or whatever, and we want those settings to be copied over to all live web servers. We want this to ensure that every member in the farm behaves the same, i.e. the end users get the same behaviour. If we only copy the application contents from the staging machine to the web farm machines then it’s not guaranteed that the IIS settings across the web farm will be the same as on the staging machine.

In other words the staging server is a central place in the system. It is a blueprint for all live web servers in the web farm: the code, the configurations, the IIS settings etc. available on the staging server are the ones that take precedence. It represents the most recent stage of the deployment environment. You shouldn’t go out and change the settings on the web farm servers and hope for the best. Instead, you “play” with the staging server settings and when you’re satisfied with the results you can push out the entire IIS config and its contents to the web farm.

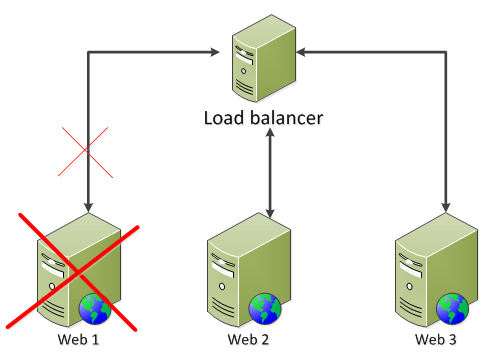

If you want to get really advanced then you can employ a PowerShell which pulls out the web server from the farm just before deploying the code to it to make sure that this machine doesn’t get any traffic during the deployment process. The script would do this to every machine in the farm one by one.

Other content replication tools

MSDeploy is by no means the only tool to replicate content. You can check out the following alternatives:

- Distributed File System (DFS)

- Robocopy

- Offline folders

- Web Farm Framework

DFS is a solution to keep servers in sync. It consists of two parts: DFS Namespaces (DFSN) and DFS Replication (DFSR). They make up a powerful tool to achieve high availability and redundancy. DFSN ensures that if one server fails then another takes over without any configuration changes necessary. DFSR on the other hand gives you the ability to replicate content over either a LAN or a WAN.

Robocopy – Robust File Copy for Windows – is a command line tool by Microsoft that will replicate content between servers, either one-way or two-way. Its main advantage is the easy-to-configure replication between folders. However, it doesn’t offer a method to redirect to the backup server is the primary server fails. With DFS this is possible to achieve.

The next option, i.e. offline folders, is rather a tool to enable the usage of offline folders which offers faster performance when the network is slow and offline files when the network is completely down. The result is that configuration files will always be available even in the case of network problems. This technique is known as Client Side Caching (CSC): in case of a network failure IIS will use the cached version until the network connection is restored.

We mentioned the Web Farm Framework in the first part of this series: it’s an advanced plug-in to IIS made by Microsoft which can fully automate the content replication tasks. We’ll take a closer look at WFF in an upcoming post.